It used to be that we had only one universe to deal with. Over the last year, however, our culture has become riddled with multiverses, metaverses, mirror dimensions and alternated realities of all descriptions.

Much of this is led by the outsize cultural bootprint of the Marvel cinematic empire. Spider-Man, Dr Strange and Loki are all encountering alternative universe versions of themselves these days. There is also the What If…? animated series, and whatever it was that happened in WandaVision. But the multiverse craze is more widespread than just Marvel.

The Flash is due to meet alternate universe Batmen, if that’s the correct plural, in his upcoming film. The next series of Star Trek spin-off Picard is set in an alternate timeline, and Doctor Who travelled to the space between this universe and the next in Flux. Even the Daniel Craig James Bond films are now said to be a different universe than that of earlier Bond films. Facebook has become Meta, in the belief that we’ll all desert our current reality for a VR universe of their making called the metaverse. Silicon Valley TechBros are currently obsessed with building this metaverse, to the extent that when Microsoft bought Activsion Blizzard for $68billion, they did so to ‘provide building blocks for the metaverse’. $68billion is a lot of money to invest in your virtual universe, especially if, as the The Matrix Resurrection told us, we’re trapped in a fake metaverse already.

Suddenly, we no longer bat an eyelid when characters find themselves in another universe, or someone from a different universe pops up in our favourite shows. When many varied elements of culture suddenly all converge on the same idea like this, it’s a sign that perhaps something deeper is changing.

As I mentioned in Stranger Than We Can Imagine, the concept of multiple universes was first dreamt up ‘after a slosh or two of sherry’ by the American physicist Hugh Everett III in 1954. He was trying to make sense of quantum mechanics, which was proving to be so different to our common sense understanding of reality that we were unable to even come up with suitable metaphors to describe it. The best we could do was the metaphor of Schrodinger’s Cat, which was a cat that was alive and dead at the same time. But what if, Everett suggested, instead of the cat being alive and dead at the same time, the cat was alive in our universe but dead in a completely different universe? If a vast number of parallel universes actually existed, he reasoned, then everything which can happen does happen.

The initial reaction to Everett’s idea was not good. Physicists tend to favour Occam’s razor, the principle that when there are competing explanations, the simplest is more likely to be correct. Universes are big things and conjuring one out of thin air in order to make sense of a living dead cat is quite a leap. As Everett’s idea required a phenomenal number of universes to ping into existence, he met with a lot of negativity. The multiverse, many said bluntly, was a stupid idea.

Discouraged, Everett quit theoretical physics. Clearly feeling that his life had amounted to little, he requested that his ashes be dumped in the trash after he died. He died suddenly in 1982, at the age of fifty-one. His ashes were indeed put in the bin, as per his wishes. Or at least, they were in this universe. In time, however, physicists started to warm to his multiverse idea – if only because other explanations for quantum mechanics were even more nuts.

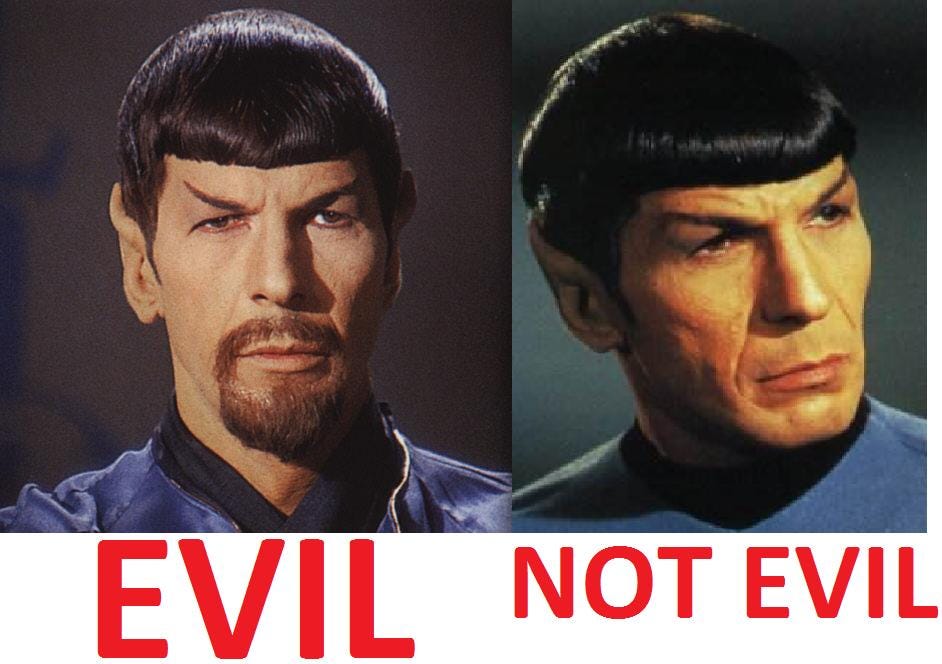

Multiverses then flourished happily in the world of comics and sci-fi, most notably in stories like DC’s Crisis On Infinite Earths (1985) and Star Trek’s occasional visits to the fascist Mirror Universe. The rest of culture, however, generally kept its distance. Multiverses were too strange and complicated for the mainstream, the thinking went. They were not something that audiences could relate to.

They were also a threat to the power of narrative. If Black Widow gives her life to save the world, then that’s dramatic stuff. But if she dies in one universe and lives in another, then the situation becomes fifty per cent less impactful. If everything that can happen does happen, then why does anything really matter? For reasons like this, Hollywood largely kept away from the idea. Or at least, it did until now.

A cynic might say that the sudden rush to multiverses is the inevitable extension of corporate brand logic – the concept of multiverses helps to keep valuable IP monetised over the long term. A more positive person might see this as recognition that the audience is actively seeking more complex and freakier storytelling. There may, however, also be a fundamental shift in our thinking taking place.

When I started work on The Future Starts Here in 2017, one of the reasons why that book felt necessary was the lack of any positive visions of the future in mainstream culture. In those mid-Trump era years, dystopian futures had become the default. You were hard pressed to find a vision of the future in which you’d want to live. Alternate possibilities - beyond the dystopian default - were then almost entirely absent.

Things have improved since then, I think, and hope and optimism are not quite as damned as they were. The rise of multiverses, I suspect, may be part of this process. They allow people to imagine different versions of our world - which we had previously been failing to do. True, much of this is currently on the trivial level of imagining that a superhero has a different face or costume. Or, is an alligator. But once we start imagining how things could be different, the possibility of engaging with the question of how things could be better suddenly presents itself. ‘The way things are’ goes from being fixed and unmovable to just one of countless options. That does change how we think about things.

There may also be another factor at play here. If the past five years have taught us anything, it’s that different sections of society behave as if they were different universes. They have different media, different values and, increasingly, a different consensus around facts. Heroes in one universe are perceived as villains in others. The differences between these universes have been exaggerated by everything from social media algorithms to media business models and Putin’s Saint Petersburg troll farms. As a result, we typically see those in other mental universes - unlike the people in our own - as foolish and morally flawed.

There is nothing new in all this, of course. We’ve always lived in different mental universes, as the history of religious wars shows. There has always been an ‘other’ to define ourselves against. But that other was usually some distance away, where it could safely be stereotyped and dismissed. The difference now is that the ‘others’ could be in our own street, or even our own family. This has brought the issue of different mental universes into sharp relief. What we used to be able to dismiss is now too noisy to ignore. These different mental universes have become, in other words, pretty hard to ignore.

The sudden cultural fixation on multiverses, in this context, may be a positive thing. We have started telling stories about passing in or out of different universes. What was once seen as unbreachable is now being portrayed as porous. Passing into or out of a universe is initially traumatic or even apocalyptic, these stories tell us. But as those stories unfold, this movement is gradually revealed to be necessary. Communication is possible between other universes, it turns out, and it is important. There is more to the other than a threat that needs to be fought.

For anyone who has experienced the loss of a friend or relative to a different mental reality, this is important storytelling. It offers hope that despite how they’ve changed, you still might one day reconnect.

It’s possible, then, that there is more to the sudden multiverse fixation than IP exploitation or a need for more complex stories. It may be that we are finally facing up to the mental multiverse that is our society, and realising that communication, not separation, is the way forward.

And if that’s not true in our universe, it will be true in another. Which perhaps we can pass into, or learn from…

Hello all! Hope this issue of the newsletter finds you well.

That multiverse essay above was adapted from my column in the next issue of MÜ Magazine - a magazine inspired by the resurgence of the Arts Lab movement. It looks like there’s a lot of good stuff coming in this issue, with Don Letts on the cover - if you’ve not come across MÜ before, it is well worth your time. More info is here.

And if all that talk of how things could be different has left you thinking about how your life could be different, my wife Joanne Mallon has a terrific new podcast series of short, practical advice on how to make changes that stick. It’s called 5 Minutes to Change Your Life and you’ll find it here.

BOOK COVER REVEALS

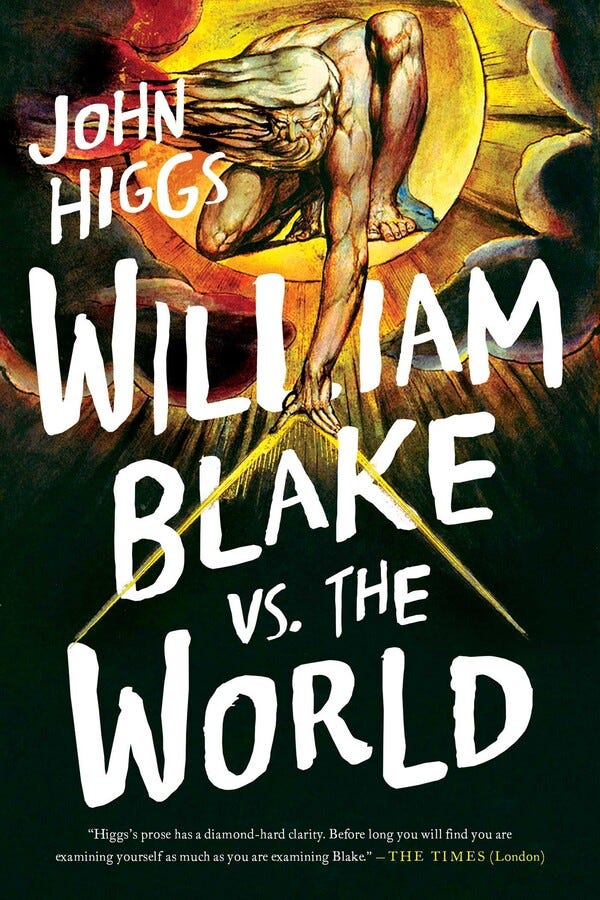

Who doesn’t love a book cover reveal? I’m delighted to report that William Blake Vs The World will be published in America and Canada on May 3rd by Pegasus Books. Here’s the North American cover:

It’s now available to pre-order from Amazon - or your preferred local bookshop.

And here’s another new cover - can anyone guess what this book is?

Yes, that’s right, it’s the Russian translation of Stranger Than We Can Imagine, of course. It is now titled “Всё страньше и страньше”, which translates literally as “Everything gets stranger and stranger”, but more accurately reads as “Curiouser and curiouser”. That will be published later this year.

I wonder what they’ll make of the thought experiment in there about Putin fighting a kangaroo?

Until next time!

jhx