Happy Summer Solstice! It’s the longest day, and in Britain this means that it’s nearly time for Glastonbury Festival to kick off. I’m very excited to be appearing this year, not least because I haven’t been since 1998 (the mud!)

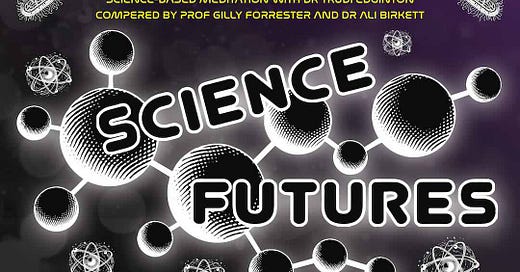

I’m being interviewed by Robin Ince about Exterminate / Regenerate on Thursday at 3pm on the Science Futures Laboratory Stage. I’ll also be appearing at some point that evening on Robin’s ‘Nine Lessons for the Summer Solstice’ event on the same stage, where I’ll be reading something appropriate from Watling Street. This looks like it will clash with Ncuti Gatwa’s appearance in the Pilton Palace cinema field, but hey.

I’ll also be in Abergavenny on 23rd August for a charity event with Keith Temple - and a Dalek! Tickets are available now - if you are in South Wales it would be great to see you there.

That will be my last Doctor Who event for the summer. Thanks to everyone who came along to a talk or got a book signed, it was good to chat to so many of you. Next up from me is the KLF book returning to its rightful state as a yellow paperback, complete with my tenth anniversary footnotes. That will be out on 17th July.

I’ll have news about my next book in the next newsletter, but I can tell you that it’s is coming pretty soon - it will be published in November.

THE BEATLES MODEL OF THE ONLINE WORLD

Like many, I’ve been obsessively checking the internet to try and follow the latest geopolitical horror show. I’ll go down into the murk of social media and emerge hours later feeling terrible, having learnt some things that are true and some things that are lies, and I kid myself that I can tell the difference. Now that AI has found a home among the outrage algorithms, the last vestiges of trust in the online world have gone and the whole thing is pointless. I want to feel informed but it leaves me feeling manipulated.

If you step back and take a wider view of the evolution of the internet, it’s surprising how much it resembles the history of the Beatles. In the early days of the internet, very few people knew about it - but those that did could see how radical, important and exciting it was. They would often feel a personal sense of ownership and its inevitable spread to the newbies was seen as both unavoidable and also a little heartbreaking. This era of the internet’s early days – a time of Usenet and ftp – corresponds with the Hamburg and Cavern Club era of the Beatles.

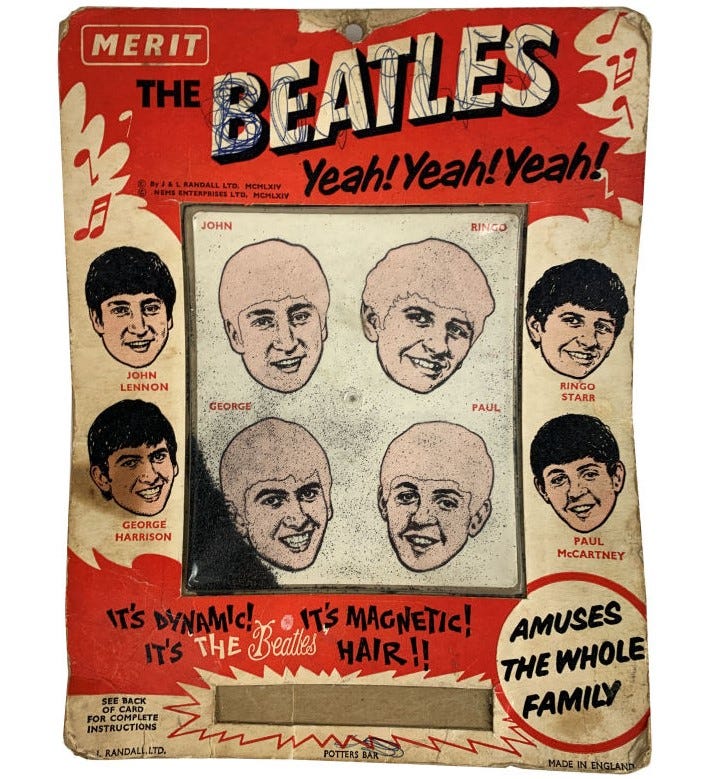

When wider society learned that the internet existed, the most common reaction was to mock. It was like early press around the first Beatles singles, which was predominantly jokes about their mop-top hair. Yet people got on board surprisingly quickly, once work email accounts led to the use of online services such as MySpace or Amazon. This period of mass adoption corresponds with the 1964 Beatles of the Ed Sullivan Show and A Hard Day’s Night. By the time Facebook was everywhere, the internet had become accepted and normalised. Much like the Help! era Beatles, it had become so central to culture that it was as if it had always existed.

But this acceptance did not mean that things were going to stop changing. There was so much potential for new things to explore and the results still felt thrilling. After the rise of Twitter and its impact on the so-called Arab Spring, it was clear that things were different and that there was no going back to how things were before. Just as with the Summer of Love and Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, the world had changed for good.

Then social networks began to divert and shape the flow of communication through the addition of algorithms, designed to maximise engagement and monetisation. Increasingly addicted to the endless scroll, the networks that we joined for communication and community started making us more anxious and isolated. And in a similar way, The Beatles became less of a single gestalt entity after Brian Epstein died. They turned into four separate individuals - as the White Album demonstrates.

Which brings us to the present day. Social media is now a never-ending stream of extreme metamodern bite-sized shocks, optimised to gain attention and provoke reactions. It swings from the banal to the evil, bombarding you with a disjointed sequence of context free content - cute animals, genocide in Gaza, celebrity fashion, hysteria about television programmes, crypto scams and AI-generated fascist propaganda. The overall effect, sometimes called cognitive whiplash, is utterly numbing.

This era is the equivalent of the medley that ends side two of Abbey Road, the last album that the Beatles recorded. This was a series of quick, unconnected song snippets following along in a seemingly random order, briefly grabbing your attention before being replaced by the next. None of them are given time to become full songs, complete enough to stand alone and reach their full potential. It’s still an amazing listen, of course – there are probably more good ideas on side two of Abbey Road than on any other side of vinyl – but it’s not something that you’d want to go on for much longer. It’s the equivalent of a diet that consists entirely of sugar. You can see the appeal, but it can’t go on like that forever.

Where could the Beatles go from there? The answer, sadly, is nowhere. After Abbey Road they called it a day - this was unthinkable, but all things must pass, as George Harrison reminded us. What had happened couldn’t unhappen and their legacy will always be with us, but it had reached its natural conclusion and it was over.

The idea that the internet is basically dying was unthinkable a few years back, but it’s increasingly hard to avoid now. It’s like discovering that your water supply has been contaminated with lead and is making you ill. Initially, you keep drinking, because you still need water. But you know you have to find a way to stop using it somehow.

Recovering our attention from the networks is not going to be easy. Parts of the digital world are still valuable and becoming entirely analogue is pretty much impossible at the moment, especially when your livelihood depends on it. But even at a time when you can’t tell truth from lies, you can feel it in your body when you’re being poisoned. You can feel your quality of life deteriorate, as you watch the Overton window sink lower and lower. We’ve probably all lost people to the online delusion, increasingly convinced that the fake online world matters. ‘So-and-so has fallen’, is a common way of expressing this. And even if parts of social media can be fixed - that’s not happening at the moment. This just leaves walking away.

Regardless of how addicted we may be - the lead is in the water, and we can’t ignore that forever.

AND FINALLY

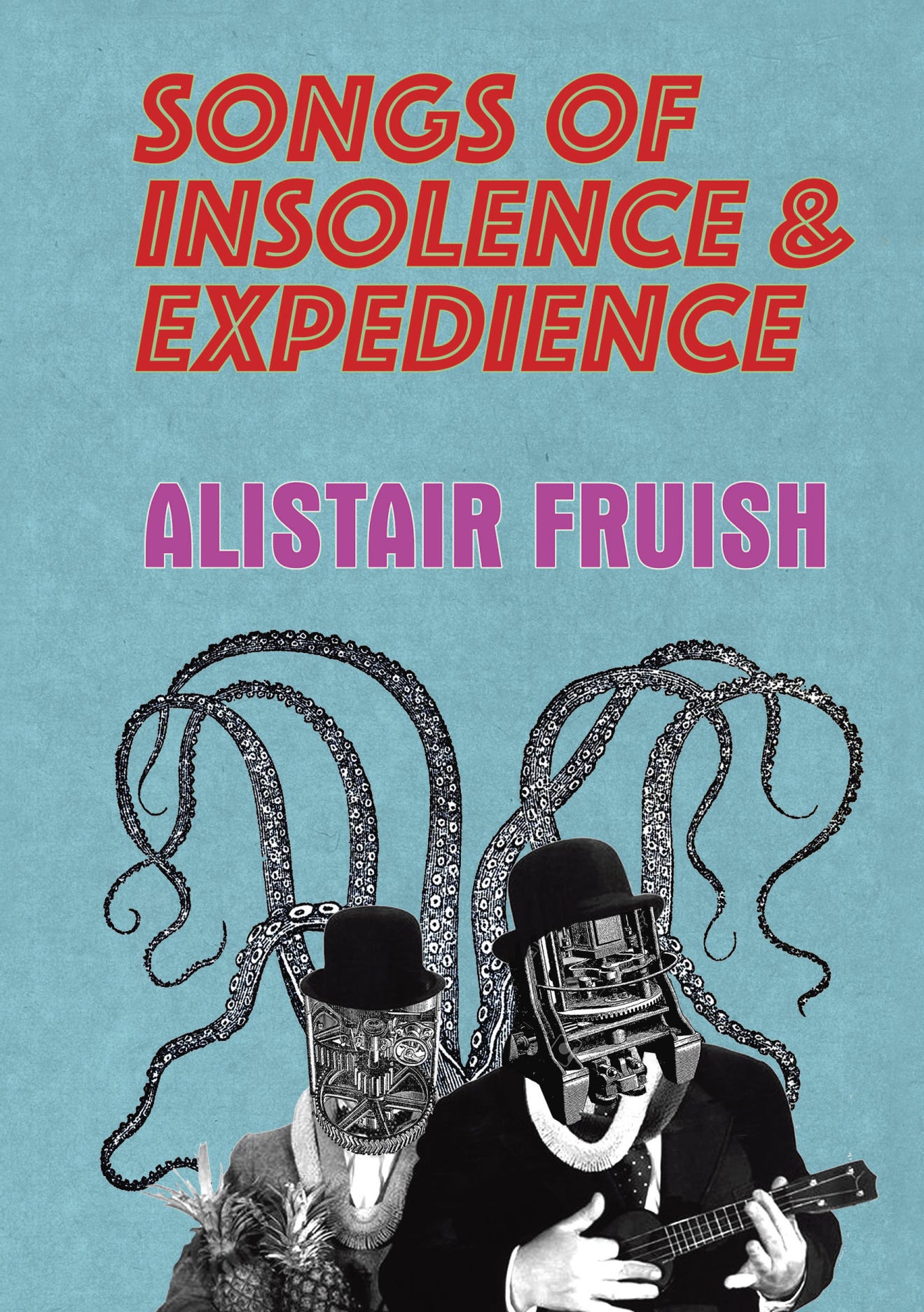

I’ve just got time before I go to let you know that there is - finally! - a new book from Alistair Fruish, who you might know as the author of The Sentence. Songs of Insolence and Expedience is a collection of his short stories from 1992-2025, and it is every bit as strange, twisted and imaginative as you would expect. It also boasts a cover by Shardcore - more details here.

Until next time!

jhx

Love the Beatles analogy John, and reflections on the grey goo internet of sewage and misery. Just makes me want to find a hammer and destroy the tech in the house!

Thank-you for your excellent book on my favourite if all- William Blake! It was written in a way that introduced Blake to the unfamiliar, but also held great interest and insights for those of us who are not scholars but are familiar with and very interested in Blake💜